For years, when people suggested that the labels should adapt their business models to the digital age and compete with piracy, but the RIAA claimed that it’s impossible to compete with free.

For years, when people suggested that the labels should adapt their business models to the digital age and compete with piracy, but the RIAA claimed that it’s impossible to compete with free.

Today the RIAA takes this notion back.

“The single most important anti-piracy strategy remains innovation, experimentation and working with our technology partners to offer fans an array of legal music experiences,” they now say.

The usage of the word “remains” is remarkable, since to our knowledge this is the first time the RIAA has admitted that innovation is more important than enforcement. But let’s not dwell on that for too long.

While the RIAA’s statement can be seen as a victory for those who in recent years spread the “innovate not legislate” mantra, it is tucked away in an article that spreads dubious claims and statistics on the effectiveness of copyright enforcement.

RIAA Vice President of Strategic Data Analysis, Joshua Friedlander, begins as follows:

“Although the impact of anti-piracy efforts often seem self evident to us, it’s important to see the real world effects, and we’re happy to see two new studies illustrating the value of these efforts in the marketplace.”

The first study highlighted by the RIAA shows that the French anti-piracy law Hadopi boosted iTunes sales. A highly controversial report, as the main conclusion is that the media buzz a year before the law went into effect was the single cause for this jump.

No third variables are seriously considered, and the authors fail to mention that digital sales actually went down in 2011, the first full year Hadopi was active. More on this in our full analysis of the report.

The second “study” isn’t really a study, but an attempt by the RIAA itself to show how effective the LimeWire shutdown was.

Using Nielsen Netview data the music group reveals that 9.5 million of the 14 million people who used LimeWire shortly before the shutdown, stopped pirating entirely. This also had a significant impact on the total number of US file-sharers.

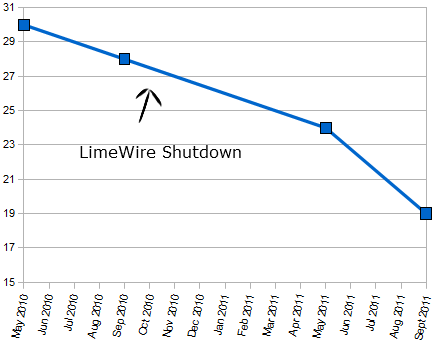

“The Limewire shutdown affected the overall numbers of users of illegal content sources. The overall number of U.S. users of the illegal sites in September 2010 was 28 million, but that fell to 19 million by September 2011,” the RIAA writes.

In other words, the total number of US file-sharers dropped 9 million a year after the LimeWire shutdown (which is +0.5 million if we discount the LimeWire users).

So far so good, but what the RIAA fails to point out is that there’s absolutely no evidence that the drop is related to the LimeWire shutdown. We doubt it, and also have some numbers to show that RIAA’s conclusion may be completely bogus.

Let’s add two more data points that former RIAA boss Mitch Bainwol shared last year.

“The number of Americans engaged in illegal music consumption fell from roughly 30 million in May of 2010 to about 24 million in May of this year,” he said.

Combining the four points, we see that during the 4 months prior to the LimeWire shutdown the number of music pirates decreased by 0.5 million a month. The 8 months after the LimeWire shutdown this average is exactly the same, 0.5 million a month.

Interestingly, there is a larger drop between May 2011 and September 2011, a decrease of more than 1 million music pirates a month. Surely, that can no longer be a LimeWire effect?

What it is, we don’t know, but something happened last summer around the same time Spotify was introduced in the US…….

And that brings us back to the innovation part.

After all, we now agree with the RIAA that innovation is the best way to kill piracy – creative statistics and overbroad censorship clearly aren’t.

Update: Innovation was mentioned here as well.