In August 2019, eight men were indicted by a grand jury for conspiring to violate criminal copyright law by running “two of the largest” pirate streaming services in the United States.

In August 2019, eight men were indicted by a grand jury for conspiring to violate criminal copyright law by running “two of the largest” pirate streaming services in the United States.

Kristopher Lee Dallmann, Darryl Julius Polo, Douglas M. Courson, Felipe Garcia, Jared Edwards Jaurequi, Peter H. Huber, Yoany Vaillant, and Luis Angel Villarino were the alleged operators of Jetflicks, an unlicensed subscription-based TV show service with a library running to an alleged 183,000 episodes.

Polo, who also ran another service called iStreamitAll, pleaded guilty to copyright infringement and money laundering charges last year. Jetflicks programmer Luis Angel Villarino pleaded guilty to criminal copyright infringement. The case against Dallmann, the alleged founder of Jetflicks, is proving less straightforward.

In a motion to suppress statements and evidence filed in April, Dallmann’s attorney describes the raids that targeted the Jetflicks founder and his husband, Jared Edwards, at neighboring properties in Las Vegas on November 16, 2017. The FBI removed Dallmann and Edwards at “gunpoint” and detained them as “agents ransacked the homes.”

“At no time was Mr. Dallmann informed that he was free to leave, nor was he provided a copy of the warrants granting the FBI authority to search his home and rental property. He feared for his own safety and the safety of his husband,” the motion reads.

After securing the suspects’ cell phones, an FBI agent reportedly asked Dallmann to unlock his, with an “armed SWAT officer” informing him he was not to touch the device but should write down the code for the FBI agents to use.

“At this point, considering that he felt threatened and obligated to comply with the FBI, and was unsure of his rights, Mr. Dallmann asked the FBI agents if he could call a lawyer. An FBI agent told Mr. Dallmann that a lawyer was ‘unnecessary’ and would just ‘complicate’ things,” the motion continues, adding this was a violation of Dallmann’s Sixth Amendment right to counsel.

Reportedly feeling powerless and under duress, Dallmann handed over the code. The FBI then asked to interview Dallmann and Edwards separately, apparently putting them under pressure to cooperate or face potentially severe consequences later on. According to Dallmann’s attorney, the FBI then obtained an agreement from Dallmann and Edwards to sign away their Miranda rights.

Under interrogation, Dallmann reportedly felt he had no other choice than to answer the FBI’s questions and incriminate himself. This included a statement that he had been advised by counsel in 2008 on how to operate his streaming operation within the law. This document, which had been seized by the FBI during the raid, was labeled “privileged” and according to the motion was outside the scope of the warrant.

As a result of the above, Dallmann’s attorney argues that all of Dallmann’s statements were rendered involuntarily as part of a “coerced custodial interrogation” and should, along with the contents of his cell phone, be suppressed.

“Upon entering the house and removing Mr. Dallmann at gunpoint, Mr. Dallmann was effectively taken into custody and detained. Consequently, Mr. Dallmann’s subsequent interview was a custodial interrogation,” the motion states, adding that the “privileged” document Dallmann received from counsel in 2008 (and his discussion of it) should also be suppressed.

“[Th]e agents continued the interview without the presence of an attorney and grilled Mr. Dallmann to further discuss privileged information. Mr. Dallmann felt that his compliance was not optional. As Mr. Dallmann’s right to an attorney had been denied, this disclosure should never have been made, cannot constitute a waiver of the attorney-client privilege in the document, and should be suppressed,” Dallmann’s attorney adds.

But of course, there are two sides to every story and the US Government couldn’t disagree more.

“The search began with a number of FBI agents approaching the front door of the residence at which Dallmann and Jaurequi [aka Edwards] lived, knocking on the door, and announcing their presence. There was no SWAT team,” the Government’s response reads.

“Either Dallmann or Jaurequi answered the door. Ultimately, both men exited the house in their underwear and stood in the front yard for five to ten minutes with Special Agent Lynch, who never drew his gun or restrained them.”

According to the FBI, an agent told Dallmann and Jaurequi [Edwards] that they were not under arrest, not detained, and free to leave but both chose to stay at the house and “seemed eager” to tell their side of the story.

“Dallmann was not taken into custody, detained, or coerced, and his statements were plainly voluntary, and his assertions to the contrary contradict the evidence in the case and that which the government expects to adduce at any hearing,” the response notes.

“The agents did not put any pressure on Dallmann or Jaurequi and they seemed very cooperative. Special Agent Shakespear described the situation as cordial. According to Special Agent Shakespear, Dallmann held his dog on his lap for part of the interview and also showed agents the chickens that he kept outside the house.”

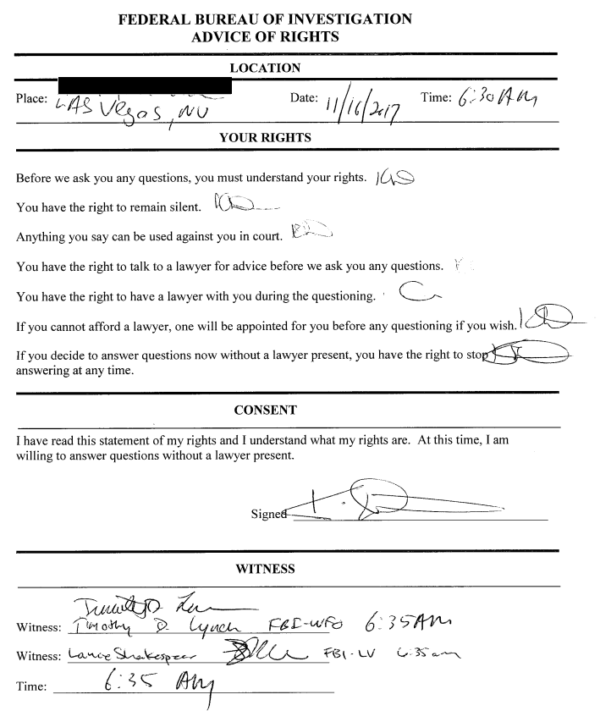

The Government denies the pair were denied their rights, noting that two blank forms with a Miranda warning were placed on a table for them to read and then sign, if they understood each Miranda right.

“At the end, Special Agent Lynch asked them if they waived each right, and, if they did, to sign the forms. Both Dallmann and Jaurequi signed the forms acknowledging and waiving each of the rights and consenting to the interview.” The image below shows the document signed by Dallmann.

The response then repeats previously reported information regarding the alleged creation of Jetflicks. It also covers the legal document Dallmann received in 2008 and was seized during the raid in 2017 – with his permission, according to the Government.

“Dallmann then said that he paid $3,000 to an attorney for legal advice on what he could and could not do to operate Jetflicks’ streaming services. According to Dallmann, the attorney gave him three categories within which he could operate,” the response reads.

“Dallmann described one category as covering the following situation: if you have content someone does not like, they will ask you to remove it; they can only sue if you do not remove it. Dallmann volunteered that the memorandum detailing the three categories would be among records seized by FBI that day.

“Dallmann consented to the search and seizure of the memorandum,” it continues.

“He volunteered information about the memorandum to the agents (who knew nothing about it before the search), described it in detail, said that he requested the memorandum and it was written for him, stated that agents would seize it, and even showed them where it was, namely, in a file cabinet in his home office.”

In respect of the cell phone issue, the Government insists that Dallmann didn’t ask for an attorney at the time he handed over its passcode and consented to a search, and didn’t ask for an attorney before or after he provided consent.

A 12-page reply from Dallmann’s attorney contests the Government’s assertions, noting that when Dallmann and Edwards spotted a line of FBI agents outside and were grabbed and forced to sit on a curb wearing nothing but their underwear, they were not free to leave. Equally so when Dallmann’s movements were restricted when back in the house, a visit that lasted 11 hours during which he never ate and his rights weren’t explained to him.

“He was never explained his rights, no officer read him any Miranda warnings, and he was not given adequate time to review the document he was forced to sign. A hearing and determination of credibility are clearly necessary for the Court to make a factual determination on this issue,” the reply adds.

Finally, a snippet from the interview with Dallmann published by the Government reveals that in 2008, when Netflix was still mailing DVDs to its customers, an apparently enthusiastic Dallmann approached the now-massive streaming service with his idea to stream content to its clients.

“Dallmann stated that he has an email from someone at Netflix stating they weren’t interested in his streaming idea,” it reads.

The documents filed by Dallmann’s attorney and the Government can be found here (1,2,3,4 pdf)